Enter Egypt's Muslim Brothers By William Dowell, June 29, 2012 |

The confirmation of Mohammed Mursi as Egypt's first president who is also a Muslim Brother triggered a 7.6% surge on Egypt's stock Exchange. That sudden boom, experienced by an economic sector that is both secular and highly pragmatic, might seem counterintuitive, but politics in Egypt are never quite what they seem.

Egypt's new president, Mohamed Mursi |

In a passionate speech to the crowds at Tahrir Square, Mursi declared that despite news reports to the contrary, the revolution continues. Whether history will prove him right, is hard to predict at this point in time. What is undeniable, though, is the fact that the collective sigh of relief that followed Mursi's confirmation is proof, if any were needed, that all parties recognize that instability is the immediate threat.

Egypt needs change, but it is in everyone's interest that the change comes in an orderly fashion. Tourism, once a major money earner, is only the icing on an economic cake that is fast crumbling because of the instability that has eroded virtually every aspect of Egyptian life. With hard currency reserves running out, and tourism at a standstill, Egypt's military, the United States, which has helped bank roll it, and the Muslim Brotherhood, itself, are ensnared in interlocking relationships that, at least for the moment, favor mutual cooperation rather than going it alone. Can one trust a president who is a major figure, albeit second choice, of the Muslim Brothers? No one knows, but Egypt's political future at the moment looks pretty much like a political hot potato, and it makes sense, at least for the moment, to let Mursi show what he can deliver.

Reflecting on her future |

The 800-lb gorilla hovering over Egypt's ongoing crisis is the fact that its population is expanding at a truly alarming rate and its expectations of having a decent life are expanding even faster. A decade ago, it might have been possible to overlook the plight of Egypt's impoverished masses, but in an age of instant communication, mobile phones and social networking, there is hardly anyone left who does not realize that a better life is possible. Mursi will not only have to deal with the inertia of Egypt's massive and unresponsive bureaucracy, he will also have to deliver results, while balancing relations with Egypt's military.

The military has long been the real source of power in Egypt, as well as one of the main obstacles to its advancement. It was the military that chose Hosni Mubarak to be its public face, not the other way around. In a chaotic social system, trying to cope with hopelessly outdated infrastructure, Egypt's military carved out a society with special privileges for itself that exists within a larger society that has been left largely to fend on its own.

Egyptian officers display goods manufactured for sale on the open market by the military |

The Egyptian military now controls an astonishing third of Egypt's economy. It enjoys its own clubs, hospitals, schools and shops, and runs its own industries. Country-wide conscription provides what amounts to near slave labor. If you are high ranking officer, it is not a bad life.

For its part, the Egypt's officer class tends to congratulate itself on the fact that it is the most viable organization in the country. A general I once interviewed in Cairo, argued enthusiastically that Army conscription is an effective means of educating otherwise ignorant villagers. They learn how to drive vehicles, perform useful occupations, and learn discipline. It never occurred to him that investing more effectively in public education might have done a better job.

With its comfortable system of privilege, the military and the sclerotic administration that served it, became increasingly distant from the reality of most Egyptian's lives. Added to that is the fact that the military's current leadership is fast turning into a gerontocracy. Field Marshall Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, the chairman of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, better known as SCAF, is 76. His deputy, Lieutenant General Sami Hafez Anan, is 64. These men clearly see no reason for Egypt's armed services to introduce a mandatory retirement age. It is hard to imagine, however, that they can really understand or sympathize with the aspirations of the younger generation that Egypt's future depends on.

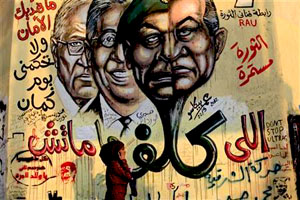

A Cairo street mural depicts Field Marshall Tantawi and Mubarak morphing into the same face |

In the 1990s, I encountered the disconnection during an interview with the mayor of Cairo, a former high ranking officer, who lived in Heliopolis, a posh Cairo suburb. The mayor casually remarked that a law restricted the heights of new buildings to the distance to the next nearest building. I asked him how he could then explain a 38-story building springing from a maze of four and five story buildings in a crowded sector on the island of Zamalek in the center of Cairo. He looked at me in amazement. "What 38-story building?" he asked. I said that it was pretty hard to miss. He called an aide who nervously confirmed that the building was indeed under construction at that very moment. What surprised me was not that yet another building had been erected defying regulations, but the fact that it was possible for the mayor of a city like Cairo to be so completely unaware of a new sky scraper knifing above the city's skyline.

Egypt's difficulty with reinventing itself is compounded by a nearly obsessive respect for authority and an desire to maintain social ahrmony at all costs. When I lived in Cairo, I often began the day by having a coffee at the Gazira Club on Zamalek. The club had an oval running track, and you would see the aging CEOs of some of Egypt's leading companies doing their daily walk around the track. The CEO would often be in his eighties and barely able to walk, but a trail of junior executives would dutifully follow behind, respectiong their aging leaders faltering pace. Despite his age, Field Marshall Tantawi regularly plays soccer with colleagues, who dutifully allow him to win each time. The obsession with social harmony is another obsession that can also have negative consequences. I once shot a film showing the environmental degradation that is consuming Cairo like a cancer. When I showed it to an Egyptian friend, she replied, "I don't want to see that. It is true, but you should not show it." In a sense, those who can maintain a privileged lifestyle, have done so by blinding themselves to what is really there.

Like most correspondents assigned to Egypt, I had found the system on the verge of collapse, only to discover that reporters had been predicting an approaching apocalypse for decades. I concluded that when the end came, it would take us all by surprise. We had effectively disconnected our alarm systems.

Egyptians today fret over whether their revolution has ended prematurely. A return to the business as usual of the past is not likely to be sustainable however. Whoever ends up assuming leadership, whether it is the Muslim Brothers or the military, will need to deal with the demographic time bomb that is the country's single greatest problem. In 1960, Egypt had a population of around 30 million people. By 1990, the population had doubled to 60 million. Today it is nearly 82 million and continuing to grow at a frightening rate. While population and expectations expand uncontrollably, Egypt's resources, and especially its agricultural land and access to water remain fixed quantities, that, or they diminish due to urban expansion.

While the Muslim Brothers are as yet untested--much as France's Socialists were before the election of Francois Mitterrand-- the Mubarak-military alliance had decades to show what it could accomplish, and in the public's perception it was found long ago to be either unprepared or unable to deliver sufficient development fast enough. There is no reason to expect a new military-sponsored regime confronting a population that is now far more politically aware to do much better. In fact there are many reasons to see military prerogatives as part of the problem. Military-owned industries compete unfairly with private sector businesses, much the way the mafia controls economic sectors in some countries. Schools, hospitals, shops and other services reserved for the military reduce the pressure on government officials to offer the same services to Egypt's society as a whole. More telling, however, is the military's insensitivity to political nuances and its readiness to rely on physical force rather than negotiation to resolve political differences.

At least in the beginning, Hosni Mubarak did not seem such a bad choice. Egyptians, jokingly nicknamed him the "gabouza,"Egyptian slang for a not very smart cow. To make their point, Egyptians who wanted to buy some French Vache qui Rit (Laughing Cow) cheese, would often ask grocery clerks to give them some "Hosni."

A package of France's Vache qui Rit (Laughing Cow Cheese) |

A cartoon depicts Mubarakas a "Laughing Cow," or Gabouza in Egyptian Arabic |

Mubarak's major drawback, and that of his predecessors, however, was to see almost any form of spontaneous non-government social organization as a political threat. This reached the point of absurdity when Cairo was hit by an earthquake in the early 1990s. When the government seemed incapable of providing relief to people left homeless, social groups centered around the city's mosques began spontaneously providing relief supplies on their own. The government reacted angrily, decreeing that only aid organized by the government would be allowed. In subsequent years, the aging Mubarak became even more inflexible. Held back by a paranoid, reactionary administration that was dangerously out of touch, Egyptian society found it increasingly impossible to deal with the basic social problems that were inevitable given its rapid growth. Neither Mubarak nor the military that supported him had the imagination, resources or the will to do it on their own.

Mubarak's regime, in short, was not so much openly evil as it was guilty of dragging the country into a kind of suspended animation that, given the pressures on it, could not last indefinitely.

As Mubarak's regime encountered more and more difficulties, it found itself turning increasingly to the outside world for support. The US was only too willing to provide technical aid on economic issues and financial aid to the military, largely as a means of obtaining political leverage, especially when it came to guaranteeing that Egypt would no attack Israel. At its core, American money became another bribe in a system already rife with bribery.

The down side to American assistance was that by prolonging Mubarak's survival the US, at least in the public's imagination, took on responsibility for Mubarak's inadequacies without having the power to actually change his inability to cope with the country's seemingly insoluble difficulties.

"We are doing the best we can with the government you gave us," A frustrated Egyptian blurted out at a US diplomat at a dinner party I attended in Cairo one night. Mubarak's failures soon became America's failures, while most Americans remained blissfully ignorant that they were now being held responsible for a wide range of evils.

The context is important when trying to understand how many Egyptians view the election victory of the Muslim Brothers. In a sense, the relationship between Mubarak's legacy, the US and the Muslim brothers, resembles a pale, telescopic mirror image of the 1928 founding of the movement itself.

The original target of the Muslim Brothers was British colonial influence, which had a disruptive impact on traditional Egyptian culture. Britain's real interest was Egypt's strategic location astride the trade route to India, but in an effort to make Egypt more economically viable it introduced modern industry and a host of other changes that displaced traditional crafts and other aspects of Egyptian daily life. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 exacerbated the influx of expats. In 1840, there were about 10,000 foreigners in Egypt. By the 1880s, the number of foreigners had swollen to 90,000, and by 1932, it was 1.5 million. In 1882, the Khedive, a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, had largely bankrupted the country and was in danger of being overthrown by Egyptian nationalists determined to drive out the foreigners. In response, the British navy bombarded Alexandria, and then defeated the Egyptian Army at Tel el Kebir.

British troops arriving in Cairo, 1914 |

TheBritish reinstated the Khedive, Tawfiq, in Cairo, but when the Ottoman Empire sided with Germany in World War I, the British decided to overthrew the Khedive and replace him with a more amenable successor, whom they declared Sultan. Egypt became a British "protectorate," nominally under Egyptian leadership, but in fact under the tight control of Britain.

In an effort to make Egypt self sustaining, the British invested heavily in the economy, and particularly in Egyptian cotton. The line between investment and exploitation was difficult for most Egyptians to discern however. A small segment of Egyptian society profited, but the sudden surge of wealth made the disparity between rich and poor much more evident. Those Egyptians who could maintain a comfortable lifestyle tended to dismiss the poverty in villages as a sign of the ignorance and backwardness that had resisted change for millennia and was best ignored.

The peasantry, and Egypt's rising middle class clearly didn't see it that way. Rightly, or wrongly, Britain was seen to be responsible for Egypt's increasingly corrupt government, its poverty and pervasive inequality. In a sense, the critics were right, British intervention had allowed an anachronistic system to last much longer than it might have on its own. Egyptians wanted to change, but to do so they had to struggle against the existing order.

Hasan al-Bannah |

In 1928, a primary school teacher, Hasan al-Bannah was assigned to teach in Ismailia, at the entrance to the Suez Canal. The parents of the children came to him one night and pleaded with him to teach them to read and write. They wanted the tools to defend themselves against the foreigners who increasingly controlled their lives.

As legend has it, Hasan al-Bannah promised to think about it, and then returned, announcing, "We are all brothers, We are brothers under Islam." The Muslim Brothers was born as a social movement.

Hasan al-Bannah's idea was to use Islamic culture and its values as a foundation for a grass roots organization to overcome foreign cultural and economic domination. His interpretation of Islam was soon criticized by local clerics, and as a result he tried to steer clear of religious issues, focusing instead on social organizing.

The movement spread quickly and was soon seen as a threat by both Egypt's elite and naturally by their foreign advisors who recognized that the Muslim Brother's agenda was on a collision course with their own.

For his part, Hasan al-Bannah had expressed a willingness to work with the government. He was assassinated in 1949 after going to a rendezvous in order to negotiate with a government minister. The minister did not go to the meeting. When Hasan al-Bannah and his aide tried to flag a taxi down to go home, two gunmen shot them.

|

The movement's next great figure was Sayyid Qtb, a talented writer and novelist, and, in contrast to Hassan al-Bannah, Qtb was a noted Islamic scholar, who worked in the Ministry of Education. Qtb spent two years at an American university in Greely, Colorado in the late 1940s and returned from the experience appalled at what he saw as American shallowness and moral corruption. In all fairness, Qtb, who never married, seemed to have a problem with women and part of the shock he experienced in America came from seeing American co-eds in Bobby sox. His personal limitations aside, he soon became the Muslim Brothers' chief propagandist and literary star. He and the Muslim Brother's both initially supported Gamal Abdel Nasser's "Free Officers" movement, which overthrew King Farouk and the Britsih-backed Egyptian monarchy in 1952. Nasser blamed Farouk's corruption for Egypt's military defeat in the 1948 war with Israel. With Nasser in power, the British were effectively out.

Initially, Nasser seemed to turn to Qtb for advice, but in fact he had planned all along to supplant the Muslim Brother's grass roots organization with his own. Nasser offered Qtb any government position he desired, but Qtb, sensing Nasser's intentions, refused. By 1953, Nasser had eliminated Egypt's other budding political parties and instituted a military dictatorship. After a failed assassination attempt in 1954, he moved to arrest members of the Muslim Brothers, including Sayyhid Qtb. Qtb was hanged in 1966, but not before completing a political treatise, "Milestones," also translated as "Sign Posts." In it, he argues that certain political figures such as Nasser are no longer part of the house of Islam, and may therefore be disposed of by violent means. Qtb's reasoned that no one could commit the atrocities that took place in Nasser's prisons and still consider himself a Muslim.

When I asked Egyptians about Qtb's advocacy of violence, they discounted his more extremist ideas as a natural reaction to the torture he had experienced under Nasser. The movement that had survived Qtb's era, they felt was far more moderate and balanced in its approach. If anything, it was too tame.

Yet during the years of repression, the Muslim Brothers has taken on the style of secrecy and labyrinthian structure of tiny cells that the Resistance in France employed against the Nazis in World War II. It is difficult to tell what those inside the movement really do intend to do.

What is clear is that the Muslim Brothers are probably as on guard against the hard-line fundamentalist Salafists as they are of the military.

Mursi has insited that he will respect democratic principles, something that Nasser failed to do. That does not mean that Mursi is likely to be pro-American. Although the US put pressure on Mubarak to step down and on the military to go along with free elections, the Muslim Brothers probably feel they have good reason to doubt the United States' long range objectives. The US gained enormous prestige in Egypt when in 1956, it blocked a three-pronged attempt by Britain, France and Israel to keep Nasser from taking over the Suez Canal, but Egyptian good quickly dissipated when the US subsequently threw its support overwhelmingly behind Israel.

Continued US support for Israel despite Washington's inability to reign in Netanyahu and the enthusiasm with which Americans supported Mubarak over several decades, makes many Egyptians question what it is that America really wants. At its most pessimistic, much of the Egyptian public tends to see the US as trying to replace the influence the British once had with a new fast-food, plastic version of dollar-fed neocolonialism, while its heart remains in Jerusalem.

Despite all of that, Egyptians realize that they need US influence in order to escape their current mess. Egypt may well need help from the IMF in the near future, and US aid and the prospect of losing it continues to have a sobering effect on the Egyptian military. The Muslim Brothers have already run into criticism for overplaying their hand by winning the election too early in the game and consequently terrifying their opposition into direct action. They will now have to produce results, or risk losing public support in the future.

The best solution in the end may be an uneasy power sharing agreement in which both sides manage to coexist. Political affiliations in Cairo these days seem to be signaled by the length of one's beard. Secularists are clean shaven. The Salafists are easily identified by their long, bushy beards. The Muslim Brothers also have beards, but they are neatly trimmed. The middle path looks, for the moment, like the one that may be the most promising.